Becoming a Non-Anxious Presence in an Anxious Generation

Just sharing wisdom on Gen Z and anxiety from John Mark Comer, Jonathan Haidt, Edwin Friedman and St Ignatius.

A repurposed/edited talk I gave for Pure in Heart, on April 30th 2025.

I have to tell you up top that I have stolen the title of this talk and much of its content. If you YouTube ‘Becoming a non-anxious presence’ you will find a much better talk given by John Mark Comer, a man who has really affected how I live my life. I watched that talk to give this talk.

This is a talk about anxiety and trying to be non-anxious.

My life currently makes me quite anxious.

The last 4 months of my life were maybe its most intense run, by sheer volume of tasks. My job is demanding and I am part-time training as a counsellor too and I need to get a placement and I am freelance producing a podcast (which helps me to be less poor as I work part time and train) and I decided to help out on an Alpha course. Oh, and essays. I was experiencing overwhelm most weeks.

Around Christmas, I started to go to sleep to podcasts. With an earphone in, I would calm the anxious voices in my head by hooking my attention to an Australian improv comedy podcast - amusing nonsense - and drift off out of consciousness. I knew that this was a red flag. I also knew that I was coping and I became ok with coping.

For years, I had lived without earphones. My image of a London douche was someone who wears a suit and always has earphones or air-pods in and is always stood waiting or commuting holding their phone, slouched down towards it. I did not want to be this person.

I screen timed the heck out of my phone so that if I was commuting I was either sleeping, reading the book I was carrying, proactively messaging (not scrolling) or just reflecting, or allowing myself to be bored, or praying, or being close to my feeling and thinking self.

When I started to sleep to podcasts, I also began to commute to them. Soon enough, I pretty much always had earphones in. I was drowning out my anxiety. Leaning on an easy comfort. Trading out the contemplative values I had developed.

So, at the off, I would like to tell you that I am no expert in the practise of being non-anxious. But boy do I have a lot of great theory I can share with you. And I’m glad that I had to write this talk right now because I think I needed to write this talk right now.

Defining our terms

What do we mean when we say anxiety? It’s Gen Z in a word - it trends in the billions on TikTok, it was the title of Jonathan Haidt’s blockbuster, law changing book ‘The Anxious Generation’ - (go buy and read this now) - it’s Doechii’s new viral track - but what does it mean? And how did it come to seemingly define our generation?

It wasn’t always this way. I recall the first time I was at a youth retreat and someone wanted to be prayed for for their social anxiety. It was a remarkably brave moment of vulnerability and the first time I had heard a young person really say that this was the primary thing they were struggling with. Now, it’s everywhere you look.

Here are some reliable definitions.

‘Anxiety is usually a natural response to pressure, feeling afraid or threatened, which can show up in how we feel physically, mentally, and in how we behave.’ NHS

‘Anxiety may be defined as apprehension, tension, or uneasiness that stems from the anticipation of danger, which may be internal or external.’ National Institue for Health

‘Anxiety is both a mental and physical state of negative expectation. Mentally it is characterized by increased arousal and apprehension tortured into distressing worry, and physically by unpleasant activation of multiple body systems—all to facilitate response to an unknown danger, whether real or imagined.’ Psychology Today, UK

We might say then that it is very close to fear, especially it seems fear of the future.

And, it’s important to note that it’s a natural response - as the NHS emphasises there. Meaning, it is not something we can get rid of. I have come by people who want to get rid of anxiety totally - if that’s you I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news, it ain’t happening. It is an emotion that we will experience from time to time. We need to listen to it, it is trying to tell us something.

Something I learned in my first year of counselling theory is that there are two separate anxiety disorders - so whilst anxiety is a natural response, it can become disordered, which is a more serious problem. The two anxiety disorders are Generalised Anxiety Disorder (or GAD) and Social Anxiety Disorder (or SAD) - sometimes called social phobia.

‘Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is a common mental health condition where you often feel very anxious about lots of different things.’ NHS

‘Social anxiety disorder, also called social phobia, is a long-term and overwhelming fear of social situations.’ NHS

Ever had a ghost flatmate? Noticed that someone is particularly reclusive, even by introvert standards? This is a thing. (Or maybe you’re just really annoying to be around, always an option… )

But, for most of us, anxiety is just a normal emotional reaction to situations in life that should make us feel anxious. Gen Z has lots of good reasons to feel anxious. Perhaps you dream of home ownership. Perhaps you don’t want to have to do National Service in Ukraine. Perhaps you work in hospitality or a kitchen (I have just finished watching ‘The Bear’ - wow the anxiety of post-COVID restaurant life). Perhaps you run a business and you just learned what a tariff is. Perhaps Greenland is up for grabs now? And Taiwan? And Palestine? And you don’t trust politicians or the media or your neighbour - it goes on.

So, you know, perhaps you have some good reasons to feel anxious from time to time.

But so did my mum’s generation, who were in school through the fear of the Cuban Missile crisis. And so did my dad’s dad who was on three ships that were sunk by German U-boats - and on by the third time he had learned to swim. My dad was born in 1948 and he recalls as a child playing around the bombed-out buildings of our town. He remarks on how he has lived in a blip of peacetime, rare in the course of human history.

So it’s not all new.

But what is new is that we do live in a strangely connected time, where we can know way beyond what our tribe designed mind can cope with. Here’s the great quote on this:

“The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall.’ Edward O. Wilson

The Anxious Generation

is a real thing, not just a catchy phrase.

It was the now late Pope Francis who set me down this path back at the 2018 Youth Synod. He referred to us as a ‘disorientated generation’ and spoke to the ‘darker realities’ that we were experiencing. It was the first time that anyone had told me that my generation was messed up. Like, unusually and historically so. And it was the Pope. So, I paid attention. When I came back to London I wanted to research this, seem if it wasn’t all hype, what some call a ‘moral panic’. For years after this I gave tentative talks about how technology, particularly smartphones and social media, might not be good for our overall well-being or our spiritual life. But, I had to say ‘there are people on both sides of this’.

Last summer, Jonathan Haidt’s book, ‘The Anxious Generation’ freed me and everyone else up to drop the tentativeness. The data is in. Social media played havoc with a generation of young people, their sense of worth and their ability to connect with others.

Perhaps most shockingly, technology made young people what they dread most: boring. As one great Substack essay title put it, ‘Your phone is why you don't feel sexy’.

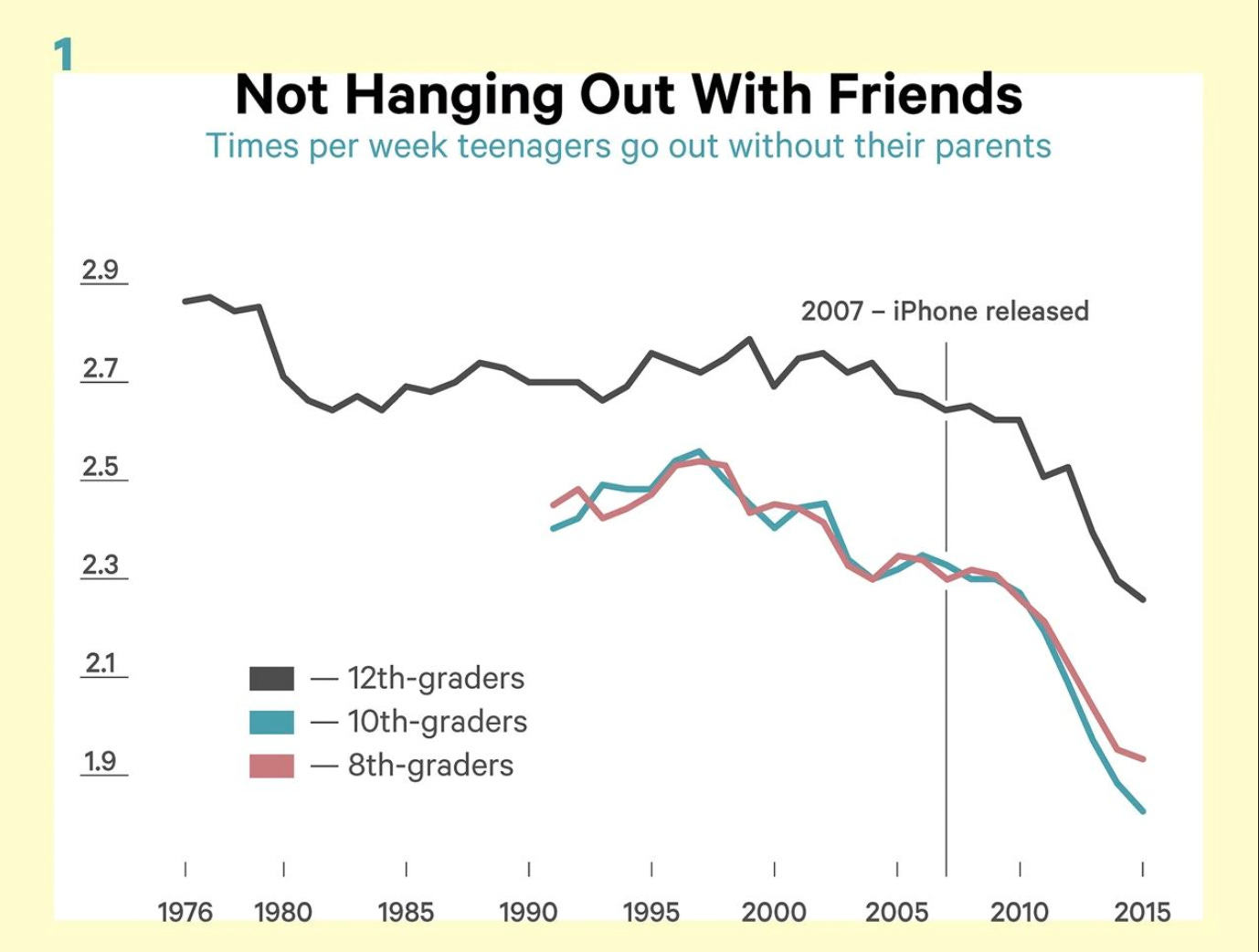

All adolescent behaviours are down, compared to previous generations - spending independent time with friends. learning to drive, dating, having sex. Less of it all. (Although I have since wondered how social researchers know how much sex people are having).

As Dr Jean Twenge, author of ‘IGen’ puts it:

‘... teens today differ from the Millennials not just in their views but in how they spend their time. The experiences they have every day are radically different from those of the generation that came of age just a few years before them.ʼ Twenge, 2017

‘At first I presumed these might be blips, but the trends persisted, across several years and a series of national surveys. The changes werenʼt just in degree, but in kind. The biggest difference between the Millennials and their predecessors was in how they viewed the world; teens today differ from the Millennials not just in their views but in how they spend their time. The experiences they have every day are radically different from those of the generation that came of age just a few years before them.

What happened in 2012 to cause such dramatic shifts in behavior? ... it was exactly the moment when the proportion of Americans who owned a smartphone surpassed 50 percent.ʼ Dr Jean Twenge

Johnathan Haidt’s essential premise is 2 fold: Gen Z has been overprotected in the real world and underprotected online.

Through the nineties there were many scares about child abduction and trust in society broke down. Previous generations of kids were told to come home ‘when the lights came down’ (think the 80’s kids in ‘Stanger Things’ biking around in a gang) and my dad in the early fifties playing around the rubble of the Blitz.

Gen Z was not allowed out of the sight of its parents until much later in life, into their teen years, and always with a phone, maybe even with ‘Find my phone’ on so they could be literally tracked. They were overprotected in the real world. They had less opportunities to learn how to navigate tough situations without their parents. They had less risky play. They had much more screen time. They literally went outside less.

When I was 14 I would come home from school and spend 4 horse, easily, on Facebook. And my parents would ask me what I was doing. And I would say I was talking to my friends and make the case that this was actually really connecting me. And I spent an awful lot more time inside because I had the option of connecting with them this way.

I also was able to come by online pornography when I was twelve/thirteen. I wish I hadn’t been able to. It is so tragic to me that so many children are saddled with the weight of shame because of this. And it goes on to harm so many relationships in the real world, really early on. If you want a pretty tough read on this, check out the 2023 UK Children’s Commissioner report, ‘‘A lot of it is actually just abuse’- Young people and pornography’.

They were underprotected online.

Underprotected from constant social comparison, from addictive design, from un-realistic body image, to name but a few. Social media was designed this way. It didn’t have to be. It’s a conscious choice by powerful companies to make us feel more anxious to hold our attention, in what’s called ‘The Attention Economy’.

‘We are more profitable to a corporation if weʼre spending time staring at a screen, staring at an ad, than if weʼre spending that time living our life in a rich way. And so weʼre seeing the results of that, weʼre seeing corporations using powerful artificial intelligence to outsmart us and figure out how to pull our attention for the things they want us to look at rather than things that are most consistent with our goals and our values and our lives.ʼ Justin Rosenstein, co-creator of the Facebook like button.

So this is new. Don’t listen to anyone who tells you that this is the same as TV or radio, or that this is a moral panic. It’s not. The graphs on teen anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide are all alarmingly sharp, especially for teen girls. And Big Tech created this situation and they made a lot of money from it and we should be righteously angry about it.

Wasn’t this talk about being a Non-Anxious Presence?

Haven’t I just given you an immense amount of reasons to feel anxious. Yep.

Partly because I now want to remind you that anxiety is a natural response. There are reasons why this generation is marked by anxiety. It has good reason to be.

So, how can we be non-anxious presences in an anxious generation?

Well, this phrase comes from a different book, Edwin Friedman’s ‘Failure of Nerve’.

In short, Friedman was a Rabbi, a therapist and an early expert in family systems theory. This theory is the basic idea that relationships function together in a system and he applied this to larger systems beyond family, such as churches, synagogues, companies and nation states. His basic premise was that whilst the West was progressing in many ways (medically, scientifically, technologically etc), the data showed that it was regressing emotionally and relationally. He has 5 characteristics by which you can know an anxious system.

‘Five interlocking comparisons are made between highly anxious, regressed families with acting-out children, on the one hand, and the functioning of contemporary American society, on the other. The fire aspects of chionic anxiety are reactivity, herding, blaming, a quick-fix mentality, and lack of leadership - the last not only a fifth characteristic of societal regression but one that stems from and contributes to the other four. Each of these perverts natural principles of evolution, namely, self-regulation, adaptation to strength, the response to challenge, and allowing time for processes to mature.’ p24

In his work as a family therapist, working with families in crisis who are experiencing system-wide anxiety, Friedman would look for the one person with the potential to become a non-anxious presence. He became convicted that the only way to stop system wide anxiety in relational systems was to insert a non-anxisous presence into the heart of it. He often called this a ‘well differentiated leader’.

‘without question the single variable that most distinguished the families that survived and flourished from those that disintegrated was the presence of what I shall refer to throughout this work as a well-differentiated leader.

… by well-differentiated leader … I mean someone who has clarity about his or her own life goals. and, therefore, someone who is less likely to become lost in the anxious emotional processes swirling about. I mean someone who can be separate while still remaining connected, and therefore can maintain a modifying, non-anxious, and sometimes challenging presence. I mean someone who can manage his or her own reactivity to the automatic reactivity of others, and therefore be able to take stands at the risk of displeasing. It is not as though some leaders can do this and some cannot. No one does this easily, and most leaders, I have learned, can improve their capacity.’ p14

So there it is. We can all just be that. well-differentiated leaders, non-anxious presences.

It’s one thing to know the theory, another to become this. How do we do it?

The Quiet Place

At the end of his book, Friedman talks of his own crisis, in which his theory was put to the test. He went through the experience of mysterious pains, numbness and tinglings and had to meet with a lot of doctors about potential diagnoses, plans and surgeries. He bullet points some methods that pulled him through, kept him non-anxious.

‘I practiced … deep breathing. Biofeedback specialists have found that like meditation or prayer, deep breathing can keep you focused on yourself, and it has the additional advantage of oxygenating the blood. (I even tried it on the operating tables before going under.)’ p244

His further principles in times of crisis are:

Develop a support system outside of the work system, such as professional helpers, family, and friends.

Stay focused on long-term goals

Practice deep breathing, prayer, or meditation.

Listen to your body.

Work out the balance between being responsible for self and being labelled obstreperous.

Keep the system loose through humor.

It's time to make decisions when the same question brings no new information.

Accept the possibility that your own functioning brought it on, which means that you may be able to influence your recuperation.’ p245

There’s a lot here, but prayer is in there a bunch.

And I could keep it that simple.

Jesus often went off to pray on his own and taught others to pray in ‘the quiet place’. Sometimes, it is translated that Jesus went off to pray in a solitary place, or wilderness, or desert. The root Greek word used is eremos. Why? St John Chrysostom tackled this.

‘For what purpose does Jesus go up into the mountain? To teach us that loneliness and retirement are good when we pray to God. He is continually withdrawing into the wilderness, and there he often spends the whole night in prayer, teaching us earnestly to seek such quietness in our prayers, as time and place may confer. For the wilderness is the mother of quiet; it is a calm and a harbor, delivering us from all turmoils.’

When my life goes into crisis mode, prayer is the first thing I drop, even though I know it grounds me.

I know that I always have 10 minutes, even in the most intense times. I can always find 10 to sit with the gospel of the day. I journal when I pray, it keeps my thoughts from drifting, focuses me up. I recommend that. I’d also recommend a time limit - 10 minutes, that also keeps your mind focused. The deep breathing too, slowing your body down.

And here, we’re talking about contemplative prayer.

What does contemplative prayer look like? Feel like? I love this famous story, featured in John Mark Comers’ ‘Practising The Way’.

‘The retreat leader and spiritual director Marjorie Thompson tells the story of a conversation between an eighteenth-century priest and an elderly peasant who would sit alone for long hours in the quiet of the church. When the priest asked what he was doing, the old man simply replied, "I look at Him, He looks at

me, and we are happy,"

This is the apex of Christian spirituality. Saint Ignatius of Loyola once called God "Love loving.’ In doing so, he spoke for the millions of contemplatives down through history’ p46

It’s just about being with God. This tends to slow you down. It tends to make you feel ok. We call on the Holy Spirit and he tends to come and be with us. Then, it’s just about us showing up. As we are. Thomas Merton has a great quote about sincerity in prayer.

‘The most important thing in prayer is that we present ourselves as we are before God as he is.’

He mets us there, and tells what he told the disciples in the storm: do not be afraid. Anxiety is fear about the future. If we have faith, anxiety is our opportunity to lean in. To trust.

If we practise this, if we maintain the quiet place every day, we will be less easily thrown off course by the storms. John Mark also points out we’ll be less easy to tempt, to stumble into our bad patterns and coping mechanisms.

‘It is very hard to tempt well-rested, emotionally healthy, happy people. It is very easy to tempt exhausted, burned-out, workaholic people under chronic stress. How often do we do most of the enemy’s work for him?’

So, (at my best) I pray when I get to the office. I’m terrible at getting up early so I’ve given up that battle. I get to work, I get a coffee and I go sit. Before the siege of the daily whatever comes in, I connect. I try to show up. I have often drifted away from this daily rhythm, but I come back.

One prayer I have found powerful comes from anonymous addict circles. It turns out that most addicts in those rooms are concerned with work and stress and anxiety and are very sure to maintain their peace in case they wobble into their coping mechanisms again. The prayer they pray is called ‘The Serenity Prayer’ - it goes like this:

God grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

Don’t duck your feelings.

One last note. A final helpful spiritual key is handed to us by St Ignatius of Loyola.

Known as ‘Ignatian Indifference’ it is better translated as a kind of freedom. It doesn’t mean you don’t care, it means that you are free on an emotional level from the need for your life to go a certain way. Not stoic, or repressed. You feel your feelings but they don’t disturb your peace or joy, because these come from God.

At the beginning of the Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius writes:

‘We should not fix our desires on health or sickness, wealth or poverty, success or failure, a long life or a short one. For everything has the potential of calling forth in us a more loving response to our life forever with God. Our only desire and our one choice should be this: I want and choose what better leads to God’s deepening life in me.’

Ok, let’s finish where we started - podcasts - drowning out the anxious voice.

I was using podcasts to numb. Numbing doesn’t really get rid of anxiety, and, as Brene Brown puts it, ‘when you numb, you numb everything’ - the good and the bad.

In a world of noise and an attention economy, what we give our attention to matters, it is what we become.

Last week, anxiety came for me again. Even though I’d prayed in the morning. I went and found the breakroom sofa and closed my eyes. And I felt its weight on my chest. And I felt like I was underwater. My timer for 8 minutes went off. I hit it for another 8. Then another 15. By then, a colleague friend sat next to me as a joke, and the future I was worrying about cleared a little. Then I went back to work on doing my part in making what I was worried about better. And I cleared more than I thought I would be able to.

I didn’t duck the feeling. I didn’t plug in the podcasts to drown it out. I let it wash over me. I felt it all. I was meant to. This is how God made us.

I’m gonna leave you with one last quote.

‘Bad times, hard times, this is what people keep saying; but let us live well, and times shall be good. We are the times: Such as we are, such are the times.’ St Augustine of Hippo

I've had this saved in my inbox for a couple weeks now, waiting for a free moment to comment. I've been battling my own increased anxiety for a year, and it flared up a lot last month, so this came at the perfect time. I actually felt some of my anxiety dissipate as I read—I think just the reminder that I'm not alone in it is so calming. I too have found myself relying on podcasts to go to sleep and don't love that trend so this was convicting (in a helpful way!). Love the focus on the practice of contemplative prayer, even just for five minutes a day. Thank you, Isaac!